Yolanda López: Artist Provocateur

La Maestra Yolanda came to UCSB for three days in mid February, 2020. She met with students, faculty and community members informally and in the classroom. The main intention of her short residency was to record a retrospective interview conducted by Celia Herrera Rodríguez and Cherríe Moraga. The candor and the courage of Yolanda López' reflections were very moving for all those present. She shared some key formational moments of her personal & political history that had never been told publicly.

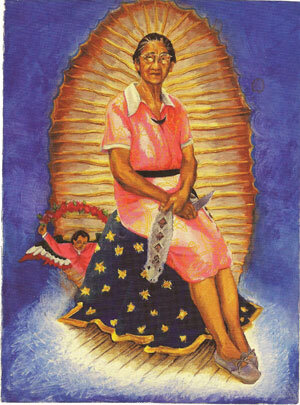

Her history of activism as an artist-organizer during el movimiento and the uncompromising avant-garde feminism of her “Guadalupe” series precedes — and provides unflinching Chicana feminist example to — present-day “artivists” movements.

“It has been our long wish to be able to bring Yolanda López to this campus and also to this idea, wherein, after decades of teaching practice, we come to think of ourselves as “Maestras,” not only as Teachers, but also Artists. And, if there is anybody that we can say has set that precedent for us as Chicanas, who is indeed for us and the country, a Master Artist and Teacher, it would be Yolanda López.”

— Cherríe Moraga (Interview: February 12, 2020)

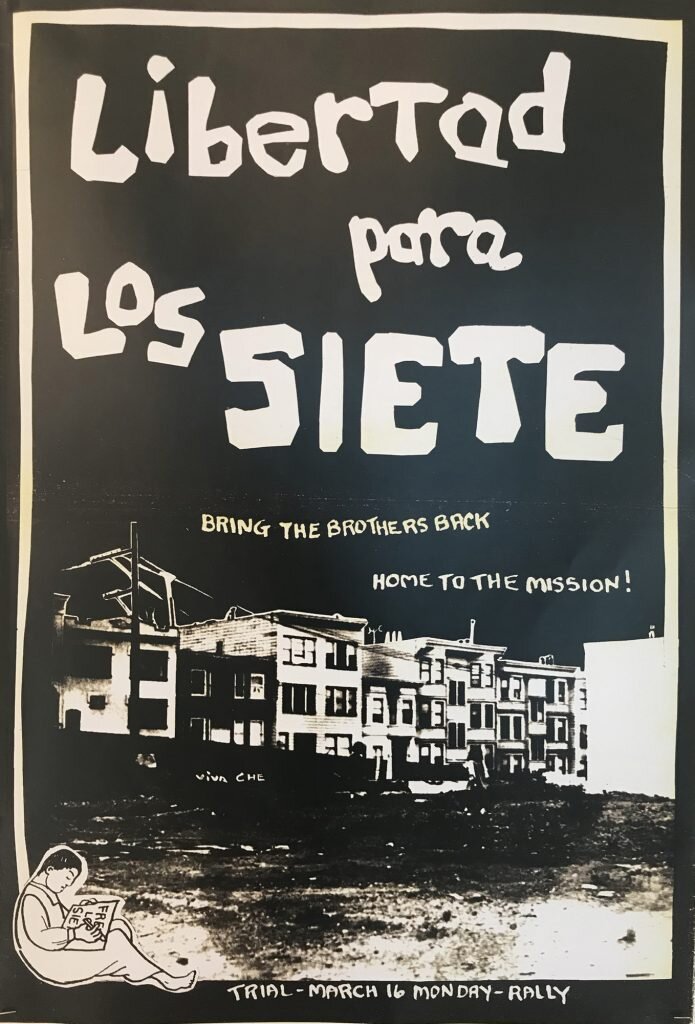

After finishing high school and moving to San Francisco in 1968, Yolanda López became an organizer for the San Francisco State University Third World Strike. The movement recognized the cultures, politics and ethnicities that were present, but never acknowledged by academia. Her political activism and Chicano roots in Logan Heights, San Diego influenced her work as an artist when she received her B.A. in Painting and Drawing from San Diego State University. In 1979 she received her Masters of Fine Arts in Visual Arts from the University of California San Diego. As Kimberley Crenshaw was coining the term “intersectionality,” Maestra Yolanda’s art work was also creating conversation about the injustices within class, race, gender and queer identities.

After her return to the bay area — in San Francisco where she now resides — her art work and activism continued to be intersectional as it often commented beyond the Chicano movement and the second wave of feminism. Maestra Yolanda’s work became one of the artistic voices fighting to use art for women of color feminism.

“The Third World strike was the idea that there were many cultures, politics and ethnicities within the world, specially within the state college system and the curriculum; that there was nothing being taught about being Native American and very few Black Studies . . . there was no discussion of any of the contributions of Black History, we are still beginning to discover things, there’s a cadre of scholarship that is woking on it . . . but also Latinos, Mexican Americans.” — Yolanda López

(Interview: February 12, 2020)